Everlasting Harmony - The Big Issue in the North

Graham Nash went from the back streets of Salford and Swinging Sixties pop group The Hollies to living the Californian dream as a multi-platinum rock star. He talks to Roger Ratcliffe about his long, strange trip

Graham Nash was taking selfies long before they were invented. A self-portrait from his spaced-out hippie period circa 1972 adorns the cover of his autobiography, and on the back is one from this year looking distinguished but slightly incredulous to find he has lived long enough to tell his wild tales.

More images taken of himself are scattered throughout the book, and when he arrives for our interview at a record store the first thing he does is whip out a compact camera to capture his reflection in a window. It’s a frequent and life-affirming ritual for him.

The grand conclusion Nash has drawn from his 71 years, he says, is that every second of every minute has to count. Like his musical partners Stephen Stills and David Crosby, he has defied the odds and survived some of rock music’s most legendary excesses of cocaine, which, you get the impression from his book, must have sustained the economies of one or two South American countries. But while Stills and Crosby are virtually walking miracles of medical science Nash looks and sounds in amazing shape, and his powers of recollection expose the myth that if you can remember the sixties you weren’t really there.

“I still have a brain!” he reacts half indignantly to the suggestion. “I mean, I got as fucked up as my partners and I’ve had an insane life but it doesn’t seem to have affected my memory.”

And it’s memories of his journey from the British pop chart machine that was The Hollies – racking up 20 hits in seven years – to become a member of global supergroup and inventors of stadium rock Crosby Stills Nash & Young that make his book almost a defining document of 1960s and 1970s music culture.

Nash grew up on the corner of a classic redbrick Coronation Street-like terrace in Salford, which he describes as “one of the worst slums in the north, maybe in all of England”. His father worked in an engineering factory, his mother in a betting shop, and most of his relatives lived nearby. It was one big extended family stuck in a “northern gulag”, he says, and he used to think there’d be no escape from a life of factory drudge until he was finally given a gold watch and sent home.

But he did find an escape route, in his head at first, when at the age of 13 he heard Lonnie Donegan’s skiffle records, then Gene Vincent’s Be-Bop-A-Lula and early Elvis songs. “I wanted that,” he says. “From that moment on I wanted nothing else.”

Soon, Nash and his best friend from childhood, Allan Clarke, were mimicking the tight harmonies of the Everly Brothers. So strong was their obsession that when the American duo visited Manchester to play at the Free Trade Hall, Nash and Clarke staked out the front steps of the Midland Hotel for hours to get a brief chat with their heroes. Never mind that they missed the last bus and had to walk nine miles home in the rain.

Their first public performance earned them ten bob each – 50p in today’s money – at a workingmen’s club, then they billed themselves as Ricky and Dane Young to play dates around local pubs, dance halls and coffee houses. It wasn’t long before they put together a group, The Fourtones, who in 1962 came within an inch of being rechristened The Deadbeats because the Commer van they borrowed to transport their equipment was owned by a mortuary. Just in time, someone – no one remembers who – suggested they name the group after one of their favourite singers, Buddy Holly.

Nash helped write many of The Hollies’ catchy confections like Stop Stop Stop and On A Carousel, but at the height of their success he quit. On a US tour, he says, he had stepped off the plane in LA, climbed up the nearest palm tree and declared to Clarke that he was never coming down. It was a metaphor the band didn’t heed, he maintains. He had fallen in love with California, and smoking his first joint there only increased his disaffection with life back in London. “The other Hollies were strictly pub guys. They had their eight pints a night to get their jollies. I felt like we were starting to drift apart.”

The rest of the group’s desire to record an album of Bob Dylan songs in the style of a Las Vegas cabaret was the final straw, Nash says. Even then he might not have been bold enough to walk out but for the fact that he’d visited the LA home of singer-songwriter Joni Mitchell in the summer of 1968 and joined ex-Byrd Crosby and ex-Buffalo Springfield Stills in an impromptu singing session.

“Something magical had happened, and we all knew it,” he says. When finally he made the decision to relocate to California it was made easier by he and Mitchell falling in love.

Their relationship turned out to be as ephemeral as most in the crazy world of LA rock music but it gave Nash one of his best songs, Our House, in which – like one of his photographed reflections – he captured a moment of their domestic bliss.

Another of his finest compositions, Teach Your Children, he began writing at a motel in South Leeds during his last days with The Hollies and was a stand-out track on the first album the trio recorded with Neil Young, Déjà Vu, which made Crosby Stills Nash & Young one of the world’s biggest groups.

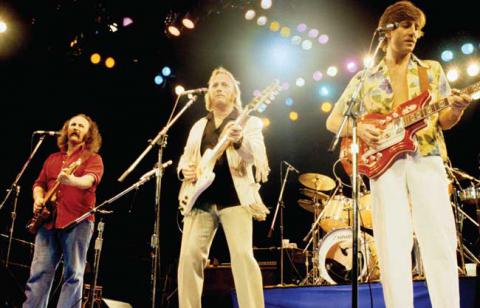

Nash’s radical song Military Madness became an anthem of the anti-Vietnam War movement and helped kickstart a successful solo career, but it’s for playing with Crosby, Stills and the frequently absent Young that he is best known. Despite Crosby’s liver transplant and Stills’s prostate cancer scare, the trio have just been in the UK pulling off the remarkable feat of turning in note-perfect performances of the famous harmonies they captured on their first album back in 1969.

Most groups would’ve disbanded decades ago after the kind of arguments they endured. At one point Nash started dating Stills’s girlfriend Rita Coolidge; another time Stills took a razorblade to master tapes Nash had recorded for a solo album.

“But we’re still singing together,” he says. “We’re brothers. You fuck up now and then. So what?”

Nash eventually bought “part of a jungle” on the Hawaiian island of Kauai, where he made a home for his wife Susan and their three children, but every so often he finds himself back in Manchester. When he steps onto the Arena’s stage, he says, it is with a touch of melancholy. He’s not sad that he left, he adds, but it’s clear that some aspects of his early life in Salford still haunt him, not least his father doing time in Strangeways after buying the young Graham a camera that turned out to have been stolen.

On one visit in the mid-1970s, he remembers, it was classic Manchester weather, tossing down all day. “It was miserable and people were all huddled up, probably because of the weather, but it felt deeper than that to me. It felt that they weren’t happy with their lives, and then I began to realise just how lucky I had been and started to think how fortunate I was that my mother and father encouraged me to get into music.”

He captured the moment in one of his most poignant songs, Cold Rain, with lyrics like “Many people share, sad dreams and hopes that are stained by sulphur in the air.”

Does he think Manchester is full of people with sad dreams now?

“No. Cities go through changes.”

His face breaks out in a smile and he mentions the irony that he’s ended up going from famously wet Manchester and its 40-inch annual rainfall to Hawaii which has 450 inches of rain a year.

“The good thing is we get these amazing rainbows. And at least it’s warm rain.”

Wild Tales by Graham Nash is published by Viking (£25)