Graham Nash: Hall of Famer puts his passion on view at Rock Hall (photos)

CLEVELAND, Ohio – Graham Nash oozes a contagious passion.

It shows in his voice when he sings, it shows in the photographs he's been taking since he was a child, it shows in his sculptures, it shows in his conversation, and it shows most especially when he's explaining the stories behind the items in "Graham Nash: Touching the Flame,'' the new exhibit honoring the two-time Hall of Famer at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and Museum that opens on Saturday.

The exhibit contains the requisite things – mementos of his days with David Crosby and Stephen Stills, with whom he was inducted as Crosby, Stills and Nash in 1997, and copies of his acetates and some records with the Hollies, with whom he was inducted 2010.

But what makes it unique – and impressive – is that it's really a collection of HIS collections.

It boasts a board from a fence in the Grassy Knoll in Dallas that was at the spot where he is convinced a second or third shooter fired at President John F. Kennedy. There's Richard Nixon's letter of resignation, addressed to Secretary of State Henry Kissinger. Phil Everly's guitar has a prominent spot as well.

A wonderful portrait of him painted by one-time girlfriend Joni Mitchell fills a wall, and is accompanied by Nash's photos of her working on the Impressionist-style painting. A 1962 test pressing of the Beatles' "Love Me Do'' has a featured place. Then there's a spot in a display case devoted to the tragic events of May 4, 1970, at Kent State and "Ohio,'' written by his former bandmate, Neil Young.

A quote from Nash above the exhibit, on the main floor of the Rock Hall, explains why he is such a collector, such a passionate collector:

"It's quite simple. I want to touch the flame. I want to get as close as I can to the flame without getting burned.''

A walk through the 2,000-square-foot exhibit, which features more than 100 items from Nash's collection, is really like strolling through a history book. And in keeping with the museum's push to become more interactive, and let the artists tell their own stories, each station has a spot where the visitors can listen to Nash himself tell the story about what's on display.

But for my trip, I had the man himself as my docent, flitting from exhibit to exhibit, pointing out all the things that mean so much to him, like a series of photos taken in Lubbock, Texas, by that city's most famous son, Buddy Holly.

"You are looking right through his eyes,'' Nash gushed, the wonder – and passion – evident in his voice.

"Buddy's music is incredibly simple,'' said Nash, who was in town for a Friday night show at the Rock Hall. "If you can play three chords, you can play any Buddy Holly song.''

But the simplicity is misleading, because the songs themselves said so much, said Nash, who noted the impact Holly had even though he recorded for only 15 months before he was killed in a plane crash along with the J.P. "The Big Bopper'' Richardson and Ritchie Valens in 1959.

Another photo is clearly a Nash favorite: It's the first one he ever took where he said he knew he saw things differently than other people. Taken with an old bellows-type camera, by an 11-year-old Nash, standing at a crazy angle on a rickety chair, it features his mother, perched in a sort of deck chair, smoking a cigarette and looking off into the distance. The question, he said, is whether she is looking into the future . . . or the past?

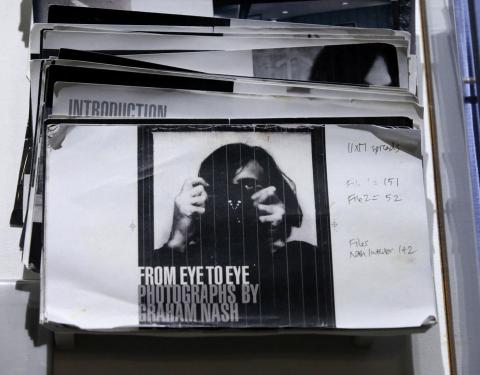

The items in the exhibit are fascinating, true enough, but it's the images taken by Nash, who noted that he's been a photographer longer than he's been a musician, that have the most real impact. That's because they're not mere snapshots; they are portraits that capture the layers of the people who are in them.

A haunting shot of a very young Crosby appears at first glance to resemble some Hollywood still for Life magazine. But stare at it, and you can almost see that the beautiful timbre in his voice is a direct corollary to his soul. That same thing comes through in a portrait of a mutton-chopped Neil Young, and it's easy to understand why Nash felt a hunger to team with them.

Here's how he said it in a quote on the wall of the exhibit:

"When I heard what David and Stephen and Neil were writing, I realized that songs had a much more important reason for existing than just trying to pick up women. . . . My songwriting changed when I came to America. I began to realize that there was more to it than 'moon, June, spoon.' That every word that you sing is important has to be true. That there were serious issues that had to be addressed in this world.''

That commitment becomes tangible in the Kent State part of the exhibit, and in a featured portion that focuses on the first Live Aid concert, in July 1985. The display shows the dressing-room assignments for the Who's Who of artists who participated, ranging from Joan Baez, who had Dressing Room A, to Lionel Ritchie, who was given Dressing Room RR.

Perhaps the most interesting aspect of the exhibit is a sound booth that lets visitors try to harmonize with Nash on one of three songs, "Bus Stop,'' "Teach Your Children'' or "Wasted on the Way.''

You can even send an MP3 of your efforts to yourself. But you might want to think twice about it.

Nash recorded several "responses'' to accompany would-be singers' efforts, including "nice job'' and one that's likely to get a greater workout: "Don't quit your day job.''

Unfortunately, the system was not up and running when I visited. But I will return to try it out one day.

See, I've got this passion . . .