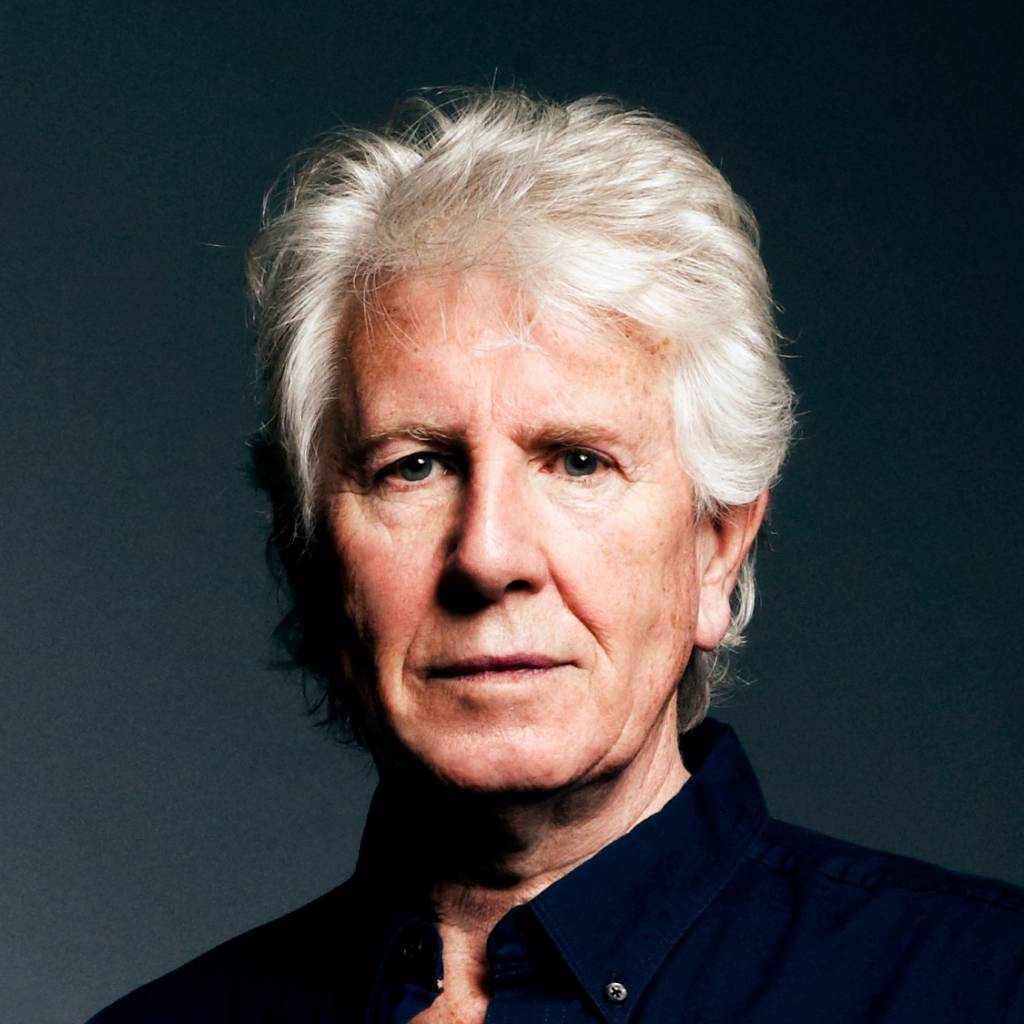

“As a musician, I’ve always reacted to my life—from the moment I open up my eyes,” Graham Nash says while prepping to release his sixth solo record, This Path Tonight, on a cold winter afternoon a few weeks into the new year. “This album is a document of a journey that I’m taking late in my life that’s stunning to me and that’s inevitable. I’m on a new path. I’ll be 74 in less than a month, providing I make it, of course. This is quite a journey for me. The music of This Path Tonight reflects that.”

It’s been 14 years since Nash released a solo album, and though he’s remained busy on the road and, occasionally, in the studio with Crosby, Stills & Nash and the Crosby & Nash duo, This Path Tonight is his most personal effort in some time. The intensely intimate batch of songs is likely the result of a late-in-life crossroads that’s unexpectedly forced him to look inward—Nash recently separated from his wife—and step into his encore years on his own terms.

Most of CSNY’s recent headlines in the press have concerned intra-band squabbles stemming from Crosby’s comments about Neil Young’s relationship with Daryl Hannah and a personal dispute between Crosby and Nash. Nash is quick to point out that he remains close with his band’s perennial fourth member. “I spoke to Neil about two-and-a-half weeks ago, when he had his birthday— and at his birthday party,” Nash says, brushing aside his involvement in that spat. However, he remains adamant that he does not want to work with Crosby—his closest musical partner for many years—and told Billboard that, “In my world, there will never, ever be a Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young record, and there will never be another Crosby, Stills & Nash record or show.” A representative for Nash confirmed to Relix that he stands by his comments.

Nash has always been responsible for some of CSN’s gentlest ballads and most universally well-known folk-pop gems, and the songs on This Path Tonight feel like natural extensions of “Marrakesh Express,” “Teach Your Children” and “Our House.”

“It’s a question of whether the music will last,” Nash says of his process, which seems to parallel his quest for inner happiness and the decision to step out on his own. “Every song that I play for you has got to get past me first. I’m my worst critic in many ways. So, I think the idea of This Path Tonight is: ‘Let’s start this journey and let’s go to the encore.’”

You wrote This Path Tonight during a relatively circumscribed period of time. What inspired this swift approach?

When Crosby, Stills & Nash or CSNY go on the road, we each have our own bus—our own little atmosphere. We travel in our little bubbles, but we do share some space with other musicians. For instance, our keyboard player Todd Caldwell will go on Stephen’s bus. I have Shane Fontayne, who is the second guitar player in the Crosby, Stills & Nash band, on my bus. It’s very hard to come down after a show sometimes—you’ve been adored by thousands and you get into these special feelings, and then, all of a sudden, there’s nobody there. So, we often go into the back of the bus and play guitar and, in a month, Shane and I wrote 20 songs together. Then, we came off the road, had Christmas, went into the studio and recorded 20 songs with a full rock-and-roll band. Though, for a couple of tracks, we actually used the demo that we made on the bus.

You’ve described “Back Home” as a tribute to Levon Helm, but you have also said that you hope the song has a universal feel. Can you elaborate on that track’s duality?

When Shane and I heard that Levon was close to passing, we decided to celebrate his life with a song, as well as physically mourn his passing, because Levon Helm was an incredible singer and an incredible songwriter and an incredible drummer and an incredible person. He played drums on “Fieldworker,” which was a song of mine from the past. Part of the art of being a songwriter is to take an incident—what was happening with Levon and what was happening in my life—and turn it into a song that everybody can understand.

Especially in the age of technology and instant gratification, listeners are searching for that sense of universalism, as well as a visceral sincerity and authenticity in music.

There’s a lot of that on this album. The version of “Myself at Last” we included is our first attempt at that song. We did a few other takes but eventually went back to the original. That raw emotion—I love that, it gets me every time. It’s real. I want to get you as close to the flame—the moment of creation—as possible given the technology. We want to record something right to tape, mix it, press it to vinyl and let you hear it. We want to put you right there, as close to the moment of the recording as possible. There have been so many times when I’ve sat there in the studio for hours, plugging away at shitty music, and then the band just comes in and plays and makes sure everything is going on the right track.

Though not a traditional concept album, This Path Tonight feels like a collective statement. Do you see a particular thread that ties these songs together?

For some reason, this bunch of songs sounded incredibly personal to me. And so I just ran with it. And Shane, who produced the album, did a fantastic job. I really love the audio quality on the record. I love the arrangements, I love the solos. So, the thread is that basically I’m the same as every other human being walking the planet. I’m doing something with my life that I’ve been doing for years, and I’m incredibly grateful and lucky to be a musician. Holy shit, what would I have been if I hadn’t turned to music? Holy Toledo, I have no idea!

I write from my life, and I think that’s the thread between all my songs. They’re stories that have happened to me. That’s all I can write about— things that happen to me or that I see around me. I look in the newspaper and I see the fact that 128 Tibetan monks have burned themselves to death over the last year and a half because of the conflict that’s going on between the Chinese government and the Tibetan people—or Michael Brown being shot in Missouri. Shane and I wrote a song called “Watch Out for the Wind”—which is on the deluxe, iTunes version of the album— the morning that we heard that Michael Brown was shot dead. My point is that I write from my life, and that’s the thread connecting all my albums.

After all these years of playing with Stephen and David, can you instinctively hear their parts when you are writing— even for a solo recording?

Yes, and “Back Home” is a particular example of that. Before my solo tour, CSN played that song and it had this slight Bob Marley feel to it. It was a rock-and-roll song. When we were recording my album, Shane came to me and said, “Do you remember our demo that we made on the bus?” And I said, “No, truly I don’t. Play it for me.” When we got to the end, I said, “Holy shit.” Sometimes you have to chase the demo—you wake up at three in the morning and you’ve got this idea, you go down to your little studio and you put it down. Then you try and do that song with the band and you can’t get that feeling that you had at three in the morning when you’re half asleep. Many times, we’ve had to overdub to the demo because the demo had that feel.

Before you started recording This Path Tonight, you worked on a series of CSN-related box sets and wrote your autobiography, Wild Tales: A Rock & Roll Life. Did those retrospective projects shape your new batch of songs?

It was a lot of looking back. I did David’s box set with Joel Bernstein, and then we did Stephen’s box set and my box set and the CSN-wide box set from ‘74. Then I wrote Wild Tales. One of the things that happened is that, when I wrote the bio, I felt like, “That was my life. Fantastic, everyone had a good time. Great, good night.” But I’ve got another path here. And I’m gonna blaze my lane to my future. And that’s what these songs represented to me. It’s like the song “Encore”—that was recorded in one take, and I particularly like the way that song feels.

You appear on David Gilmour’s new album Rattle That Lock and also sang on his previous release, 2006’sOn an Island. How has your friendship evolved?

I’ve been a fan of Pink Floyd since the mid-to-late ‘60s. Gilmour’s a brilliant musician. He is one of the tastiest guitar players I know. He can make one note last for bars and bars and bars and bars. He’s like Neil in that way, although Neil is much more rugged. Crosby and I were playing this show at the Royal Festival Hall in London with our band, and Gilmour came back after the show to talk and said, “I’ve got two things: One, I’ve got this song called ‘On an Island,’ and I want you and David to sing on it. And two, I’m stealing your drummer,” which he also did. Now Steve DiStanislao plays with Gilmour, too. I have great respect for David Gilmour, and any time he wants me to sing with him, I am right there.

Speaking of backstage interactions, Trey Anastasio recently told a story about attending a CSNY show right after Big Cypress. When you met him backstage, your first words were: “Congratulations on your success. Don’t fuck it up.” Do you remember that encounter?

Of course—the legacy of Phish and the Grateful Dead has always been interesting, musically. But I recognized that Trey is a great, great guitar player and that Phish had the ability to go on and draw 100,000 people to a concert on a mere rumor. That kind of success—that kind of power in terms of communicating music to people who love it—that’s what I told him not to fuck up. He has that power, and he’s a great musician, of course.

There’s been talk of a Rick Rubin-produced CSN album of cover songs for years. What’s the status of that project?

Here’s what happened with the covers album: We started it with our group and with Sony. We got about seven tracks into it and it just started to not work out between Rick and, in particular, David. So we went into Jackson Browne’s studio in Santa Monica and re-recorded a few songs. And there’s two or three that we really like. We will get to it. [Ed. note: Nash made his comment before his fight with Crosby went public.] We’ve just been working together a lot for the last couple of years. I mean, it took me four years of my life to do this CSNY box set. My point is that I need a rest from David and Stephen. I need a rest from that music. I need to concentrate on this new journey that I’m on.

Shifting from recording to touring, you’ve been on the road as a solo act. What does that more personal situation offer that CSN doesn’t?

In many cases, these shows are just me with the acoustic or electric guitar, or me with the piano. That allows you to take a song and break it down to the very essence of how it was created. When you take a song right down to its basics, with nothing in the way, you either have a good song or you don’t. There are no strings, no choruses coming in, none of the rest of the shit you put on records to hide the songs. One of the joys is seeing the faces of the audience and the very fact that you’re communicating with them. They’re understanding that they’re watching a human being and they’re watching a human being going through life’s changes just like they are. I think that’s a compliment—that I can express myself and expose myself and have people understand. In many cases, they’re going through the same changes I am.

I almost sculpt the setlist like a journey. I go from The Hollies to early CSN, to late CSN to David’s and my music, to my music, including songs that may have been written that morning. I see it very clearly: I’m 74, and my life is a journey. I’m loving this ride.